Van Gogh

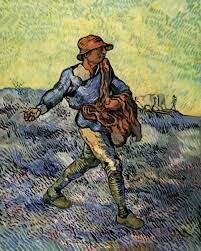

The Sower, Autumn 1888

As it has for many of my friends, the artwork of Vincent Van Gogh continuously grabs my attention, pulling me in to look at both the “big picture” of his paintings as well as the details. It is as if he has painted welcoming arms into the many layers and swirls of his paint; and as we look at his work, we walk into his invitation to see the world more deeply with him. Over the years, I have posted on Instagram/Facebook Van Gogh paintings, many times writing “A new-to-me van Gogh.” If “likes” or “hearts” mean anything, these posts resonate with many folks . . .as well as whatever tracks my likes, because I usually get more Van Gogh sites to “follow.”

Maybe it’s because we, his viewers, are drawn to his story of being a rejected, passionate, and vision-focused painter who mangled his ear. It’s not hard to forget his subject matter or his bright colors. When I wonder around a museum, I will look for his sunflowers, or his trees, or his blue skies. It could be that we remember how he titled his pieces. It is not hard to forget “Starry Night”… or all his swirls and bursts of color in this painting. His work is uniquely his own and hard to mix up with other painters. Still, when I see a new-to-me piece and realize it is him, I feel rather smart.

Along with delighting in his work, I have enjoyed learning about him. It started with reading the picture books Camille and the Sunflowers by Laurence Anholt (now titled van Gogh and the Sunflowers) and Katie and the Starry Night by James Mayhew to my daughters. Reading essays, listening to art historians, and even watching movies about his life (of course, then googling what was true and what was not). Recently, I went straight to the source and read excerpts of his letters to his brother Theo. I have been fascinated by his life, his vision, and his talent, but mostly how his Christian faith intertwined in his life and his art making.

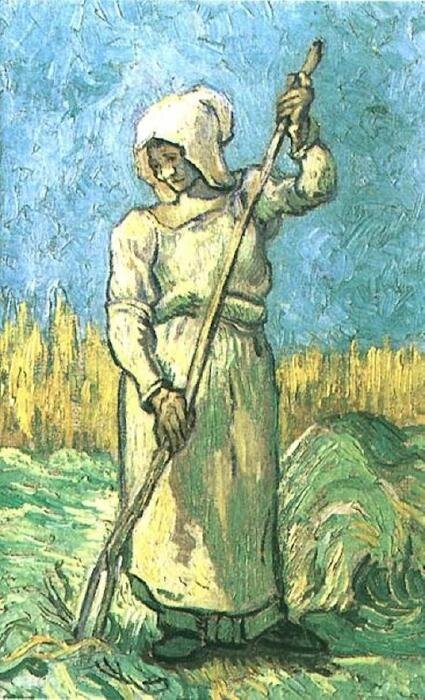

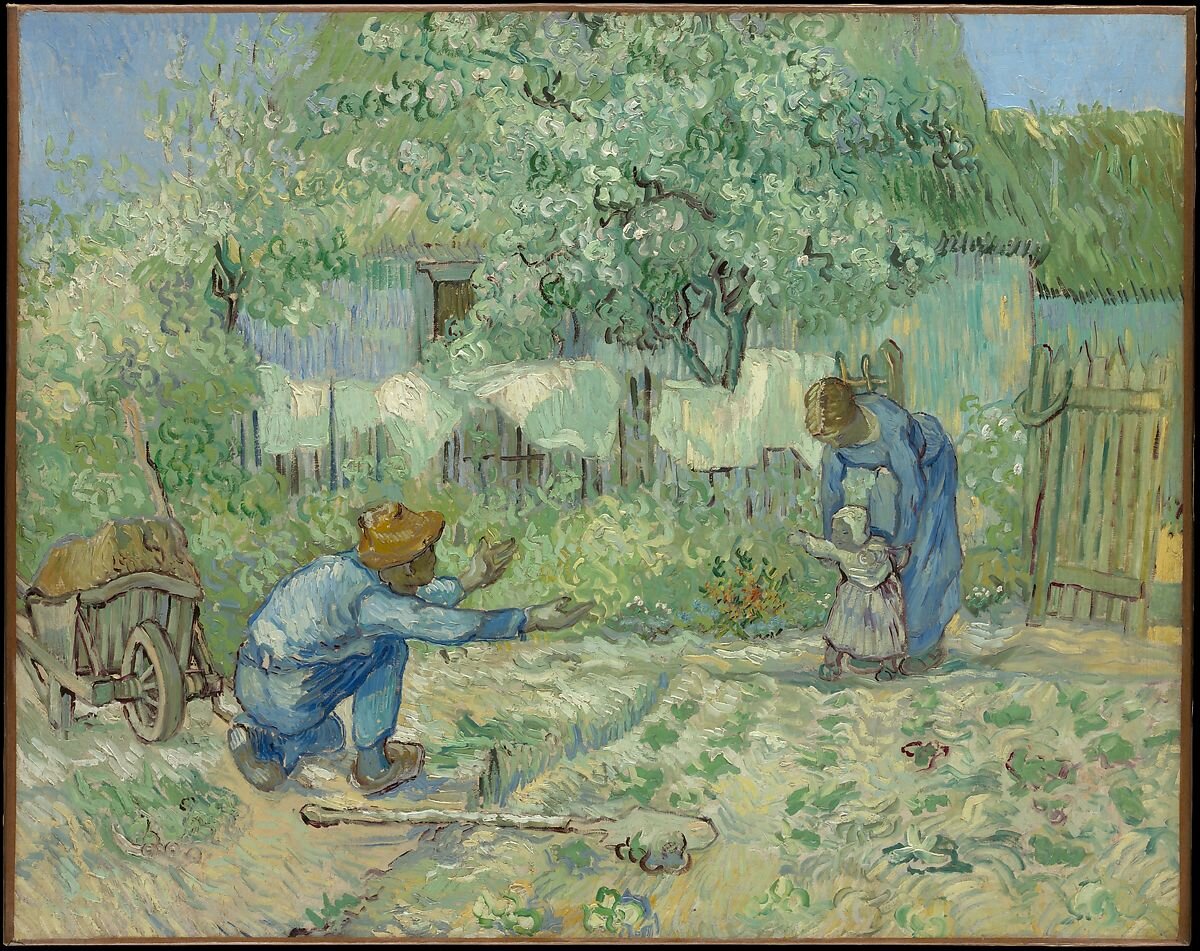

Recently, though, I realized I had missed an important influential painter to him. One day, his painting “First Steps” showed up on my IG feed. The piece is very warm and homey. A father kneels down in his yard, with his hands stretched out toward his child and wife. The wife is walking behind their little one, as they make their way towards the arms of the father. The scene takes place in their garden, under the shade of a white flowering tree. Variations of green, white, and blue, as well as earth tones, fill the scene. There are splashes of sunshine. I particularly love the little child in light pink with her arms stretched out to her father.

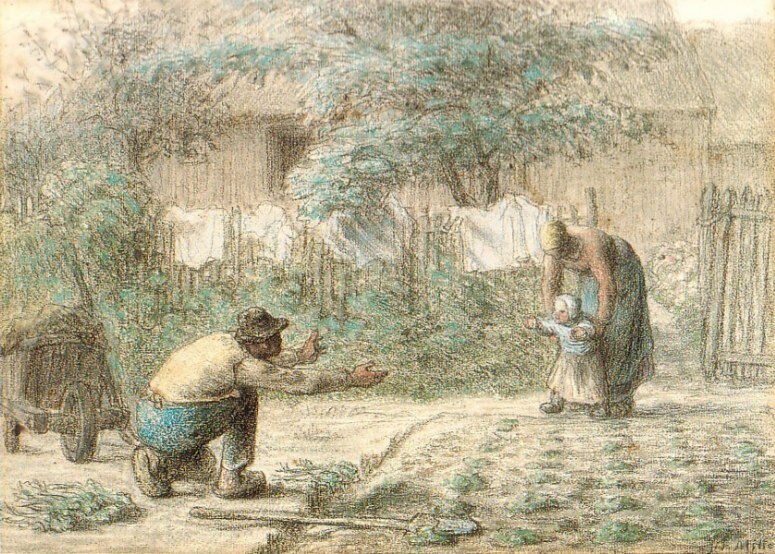

This inviting painting is actually titled “First Steps, After Millet.” It was the “After Millet” that I noticed and wondered about. Jean-François Millet’s “The Angelus” came to my mind, and so I looked up his “First Steps,” and learned that he had started this piece with black chalk in 1858 and finished it with colored pastels around 1866.

Vincent van Gogh’s “First Steps” is an oil on canvas that he painted in 1890. This piece is part of a collection of twenty-one paintings he did “after Millet” from 1889-1890. After learning this, my hunt for more paintings and research continued. To my chagrin, I learned that several of my favorites are actually those he did “after Millet”

Millet, a Realist painter, was an early influence in van Gogh’s life as an artist. When Vincent was twenty-two years old, living in Paris, he saw an exhibition of Millet’s drawings and was inspired. Six years later, as he was working on his figure drawing skills, he copied many of Millet’s prints, calling the French man, “Father Millet… counselor and mentor in everything for young artists,” as Vincent wrote Theo in 1885.

In a few more years, Millet would continue to guide van Gogh in his art making. It was not just Millet as an artist that inspired van Gogh, but Millet’s life and vision that was important to his growth.

Millet lived from 1814-1875. Although he did achieve great financial success and respect in his work, and was considered at the time one of the greats of early 19th century painting, much of his artistic life he was looked down upon by the French establishment for depicting peasants and farmers with respect. Millet showed them as being proud of their work and their land. This was seen as inappropriate at the time. In Millet, van Gogh found an artist who mirrored his own deep respect and compassion for the ordinary farmer and the down trodden peasant and the work they did with their hands.

James Romain writes about Millet and van Gogh in the essay “What the Halo Symbolized, ”A devout Christian, farmer’s son, and artist committed to dignified representations of peasant life, labor, and piety, Millet inspired Vincent as a model of an artist motivated by faith. In 1883, Vincent wrote to his brother, “The longer I think about it the more I see that Millet believe in a something on High.” He also wrote to a friend, that “Millet has painted . . . Christ’s doctrine.” By this, he meant that Millet painted with, not only in his motifs but in his method, the values of faith, love, and humility that Vincent considered most Christlike.” (page 212, Art as Spiritual Perception: Essays in Honor of E. John Walford, edited by James Romain )

For three months, from 1889-1890, van Gogh was a volunintarily became a patient at the asylum at Saint-Rémy. Here he took prints of Millet’s work and translated them into his own paintings, using his techniques, colors, and ideas. He did twenty-one “copies. “

Vincent wrote Theo about this work, explaining they were more than just copies, “"If someone plays Beethoven, he adds his own personal interpretation; in the music . . . it also counts and the composer doesn't have to be the only one to perform his compositions. Anyway. . . I put the black and white by or after Delacroix or Millet in front of me to use as a motif. And then I improvise in colour [...] seeking reminiscences of their paintings; but the memory, the vague consonance of colours while are at least correct in spirit, that is my interpretation."

At one point, Theo’s reaction to Vincent’s “after Millet” paintings was positive, saying it was some of the best work he had seen him do, and that he felt “big surprises still await us the day you set yourself to doing figure compositions.”

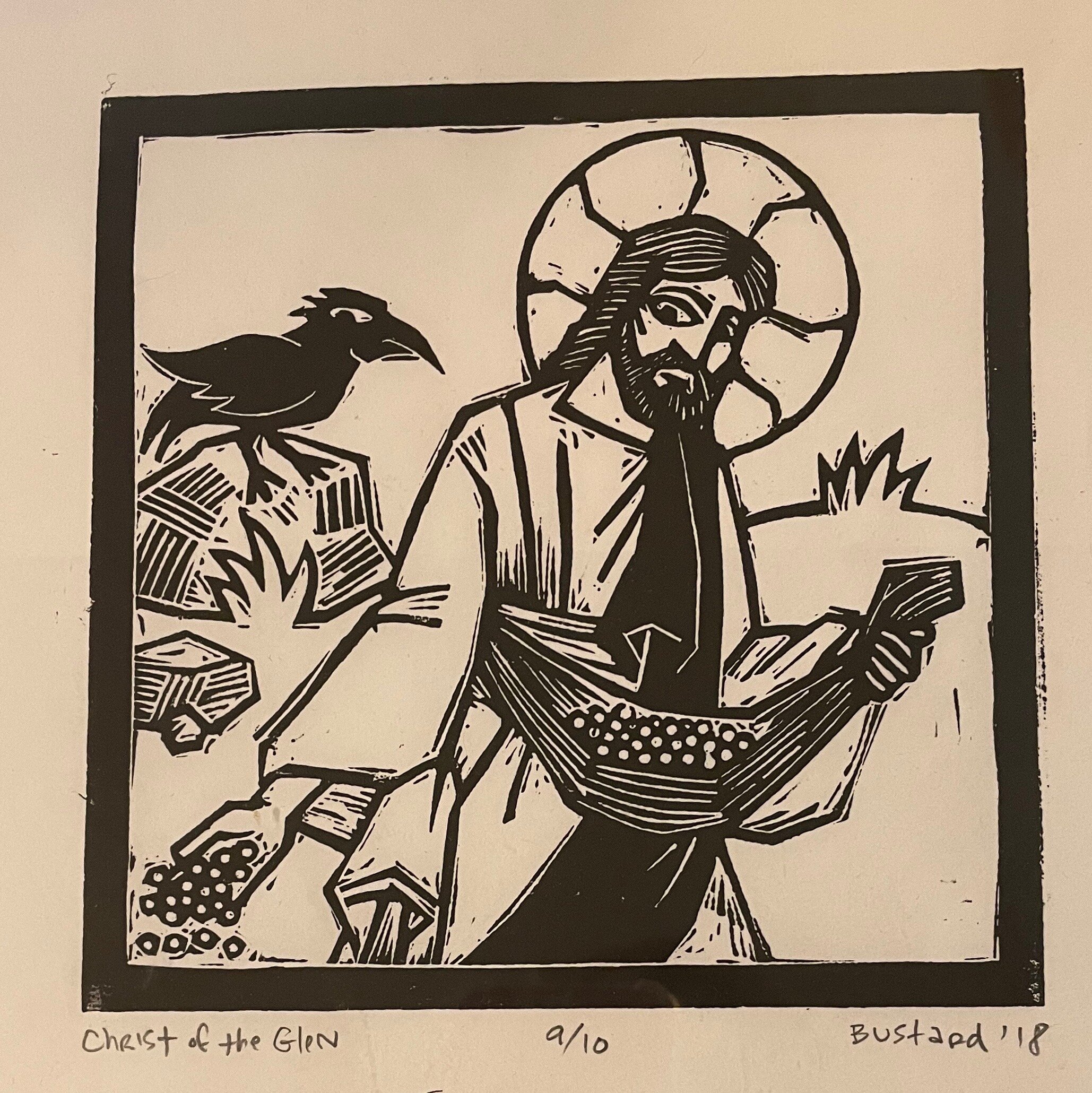

My favorite “after Millet” piece is “The Sower”; I loved this piece and the others that van Gogh did of a sower before I knew about his “after Millet” works. However, I am also taken in by how other artists I know have their own “after…” pieces of “The Sower”. A friend, and artist, Sandra Bowden has a large piece that is actually gold-leaf with Millet’s “The Sower” etched in it. But for most of the years it has been in our home, I confess I thought it was “after van Gogh.” My husband Ned has a lino-cut of “The Sower”, which turns out is “after van Gogh, after Millet.” (But the “after Millet” part is new to me.) I’m glad there is still much to learn in the world of art history and what inspires other artists.

Millet’s “The Sower” was also Vincent van Gogh’s favorite piece. During my research, I learned from Martin Bailey at The Art Newspaper, “Although he never saw Millet’s paintings of the subject, he possessed a print made after it. In 1881 Van Gogh drew a straight forward copy of the print, to practice his drawing. Seven years later, he took Millet’s figure and included it in a painting of a Provençal wheatfield. In Van Gogh’s version of The Sower, the peasant strides across a ploughed field, sowing next year’s crop, pursued by ravenous birds. In the background lies a field of unharvested wheat, ripening beneath a symbolic setting sun.”

Hanging in our home is another lino-cut that Ned created. It is Jesus as the Sower, generously sowing seed; to the left, behind him is a black bird. sitting on a large rock. Jesus is carrying a large cloth bag full of seeds. Under this lino-cut are the words of Malcolm’s Guite sonnet, The Good Ground (I think Vincent van Gogh would have liked this):

I love your simple story of the sower,

With all its close attention to the soil,

Its movement from the knowledge to the knower,

Its take on the tenacity of toil.

I feel the fall of seed a sower scatters,

So equally available to all,

Your story takes me straight to all that matters,

Yet understands the reasons why I fall.

Oh deepen me where I am thin and shallow,

Uproot in me the thistle and the thorn,

Keep far from me that swiftly snatching shadow,

That seizes on your seed to mock and scorn.

O break me open, Jesus, set me free,

Then find and keep your own good ground in me.

(I love listening to Malcolm Guite read his poetry.)

What I enjoy in Jean-François Millet, in Vincent van Gogh, in Sandra Bowden, in Malcolm Guite, and in my husband Ned, is getting to listen in on the continual conversation of artist with artists across the generations and cultures.

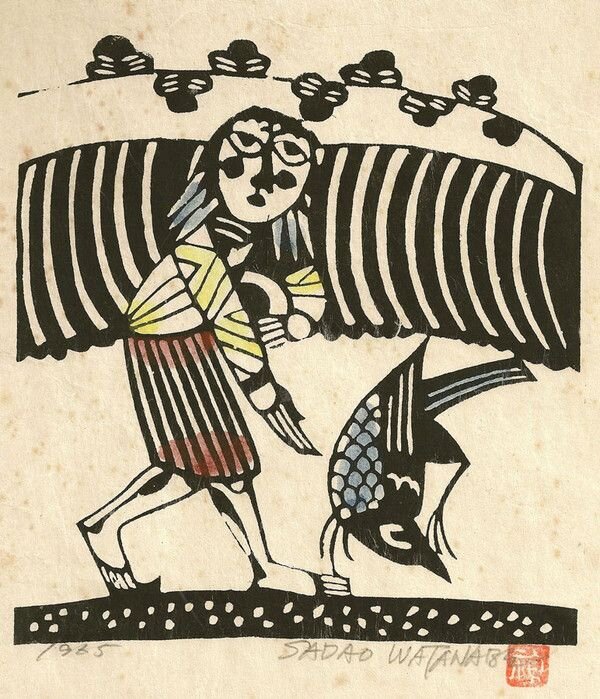

Out of curiosity, with this thought in mind, I looked up another favorite artist, the Japanese print maker, Sadao Watanabe, and found that he, too, had a sower painting. I could see reflections of van Gogh (or Millet?) in his piece. Decidedly Japanese in it’s details, the work shows compassion and respect for the farmer and the story that Jesus told. This piece is another connection, another point, in the conversation that I hear and see art makers have with other art makers, translating and expanding what they see and feel through their own choices of materials, colors, shapes, and design.

As Vincent van Gogh and Millet ( who he conversed with) and other artists (who conversed with van Gogh and Millet) have paid attention and sought to see deeply, may we learn from them to do the same - seeing with compassion, creativity, and care the people we are with and in the places we find ourselves.

Below find examples of Millet’s work and then van Gogh’s “after Millet” pieces. (The last piece is Ned’s Sower.)

Sandra Bowden’s The Sower, after Millet

Ned’s The Sower, after van Gogh, after Millet

Sadao Watanabe’s The Sower